A few years ago I did a heavy amount of researching and preparing for a lecture I gave at Costume College. I had been asked to post this to my blog, so I am finally getting around to doing it! I hope this will be a multiple part series, to help you understand how to use vintage patterns, as well as learn a little about their history. I’ll also use this as a tool to help explain what I do with Wearing History patterns, since they’re often called “reproductions”, but, in actuality, after you follow through the series, you’ll come to see how pattern companies that offer “reproductions” differ from each other and also from the original source materials.

Why De-coding?

If you’ve ever pulled out a vintage pattern that has holes instead of printing, it may seem like a giant puzzle piece. You may feel like you need a decipher to understand the markings. And the instructions can be so minimal that you may feel like you need a decoder to just figure out how to put the thing together! In this series I will offer tips for using vintage patterns based on my experiences and research.

The biggest factor that seems to dissuade sewers from using vintage patterns are the perforated, or unmarked, patterns. Let me break down a basic history of the printed pattern:

– Pre 20th Century Books & Periodicals –

Sewing patterns were available to the home sewist and the professional dressmaker or tailor in in the form of diagrams, dating back until the 18th century. These diagrams were often published in periodicals and books. Although I don’t have original 18th century sources to share, I do have original 19th century publications which I will share at a later date. Tailoring periodicals were published, and still often are, without a drawing of the finished garment, but with a layout showing the seamlines. Sleeves often overlapped, as most were two-piece sleeves. The same was true of dresses of the 19th century- certain pieces overlapped, and by grouping together, you saw which seams matched as well as what pieces went together. Peterson’s Magazine, and other fashion magazines, included an illustration of a garment and a small diagram for cutting in most issues. Other magazines, both in America and in Europe, published periodicals that included a fold out pattern sheet with many lines overlapping each other, printed on both sides, which included ten or more garments. You would have to follow dotted lines that varied per piece in order to trace out a garment. All of these types of patterns did not include seam allowance, grainlines, notches, or other markings- other than the occasional mark for a roll line of a collar and, very occasionally, button placement. Many did not even tell what size a finished garment would be. The home sewist was expected to have a very good familiarity with garment construction and basic pattern drafting in order to create their own garments. In fact, many times, a person would take this to their dressmaker and have them made for them, rather than making them for themselves at home.

Tissue Paper Patterns & The Technological Battle for Printed Patterns

In 1863,Butterick created the first mass produced, sized, tissue paper home sewing pattern. These early patterns did not include printed markings or seam allowances, but had perforations (holes) and notches cut out. Early patterns were folded tissue with a little piece of paper glued to the outside piece of tissue which included information and extremely brief, text only, instructions, an illustration and description of the finished garment, the size, and fabric requirements.

Over the next nearly hundred years, home sewing patterns went through a transformation with top companies competing fiercely to be the first to bring new technology both in the way the actual patterns were made and presented to the instructions that aided the home sewer.

In this post, we’ll primarily at McCall, one of the two big companies who led the innovation in the early home pattern market- McCall and Butterick. These two companies combined helped to create the home sewing pattern like we know it today.

McCall led the way with the printed pattern and the color envelope, so let’s take a look at the progression of changes through their company. Looking at McCall patterns makes vintage sewing seem more accessible, because even their patterns as early as the 1920s seem more understandable than most vintage patterns did up until the 1950s.

McCall started by doing perforated patterns just like every other pattern maker. By the turn of the century it was standard to include seam allowances in the patterns, though patterns of earlier times may not have included seam allowances. The home sewer would need to add them.

-McCall Patterns-

McCall Patterns originally included perforations for pattern markings, like their other competitors, but they eventually joined the competition that was part of the new, popular, tissue paper patterns, and fought to develop new technology that would give them the edge over other companies in the field.

The first pattern company to introduce printed patterns was McCall, who started printing directions on their patterns in 1919, and held the patent rights to their printed pattern technology until 1938. Even after the end of their patent, other pattern companies were slow to adapt to the new pattern printing technology and most didn’t print their patterns until the mid to late 1950s, so don’t expect that a vintage pattern you buy will have printing like those of the McCall patterns, unless you know for sure that that company used printed patterns. Usually they will say “printed pattern” on the cover, but they may only be partially printed. We’ll address that after we take a peek inside McCall patterns.

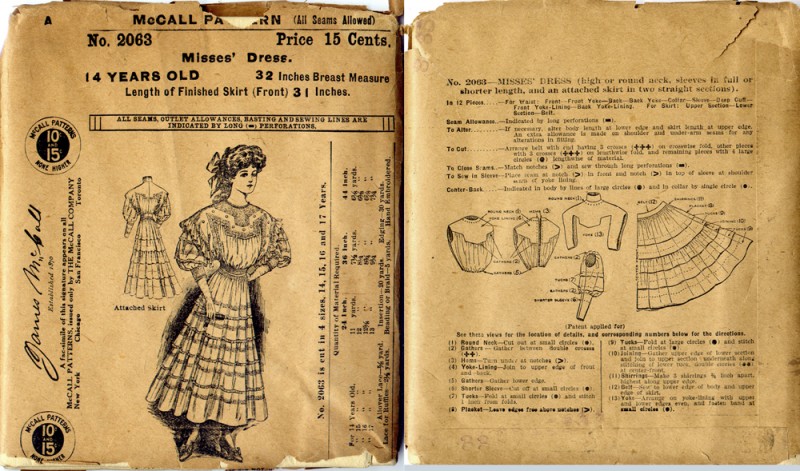

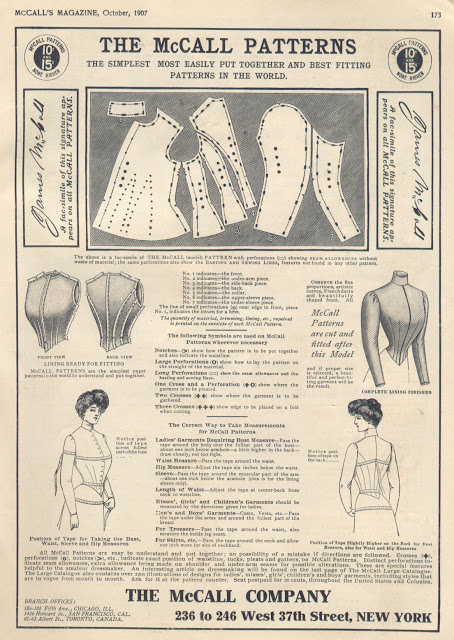

This pattern is a pattern which was published before McCall started printing on their patterns. It dates from the Edwardian era and what you see on the back cover is all you would get in terms of instructions. There are a few illustrations, which was somewhat rare for patterns this early, as most were text only. In fact, mail order patterns had instructions which were text only up until the early part of the 1930’s.

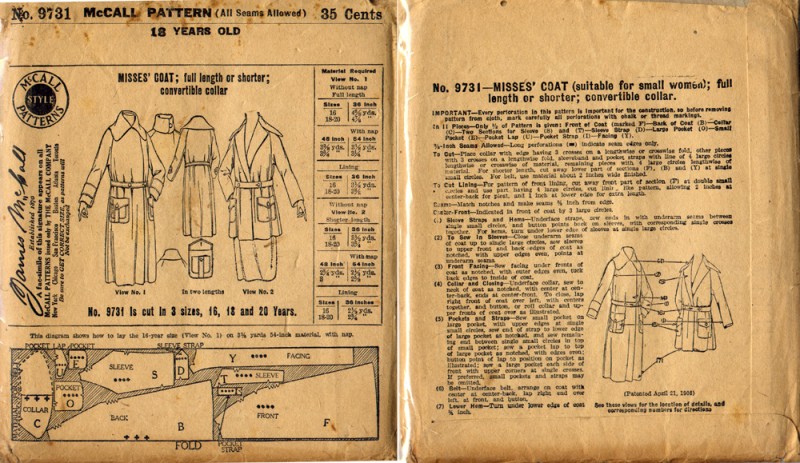

By the 1910s you can see the addition of a fabric cutting chart. These were for vintage fabric widths, of course, which are different than our fabric widths today.

By the 1910s you can see the addition of a fabric cutting chart. These were for vintage fabric widths, of course, which are different than our fabric widths today.

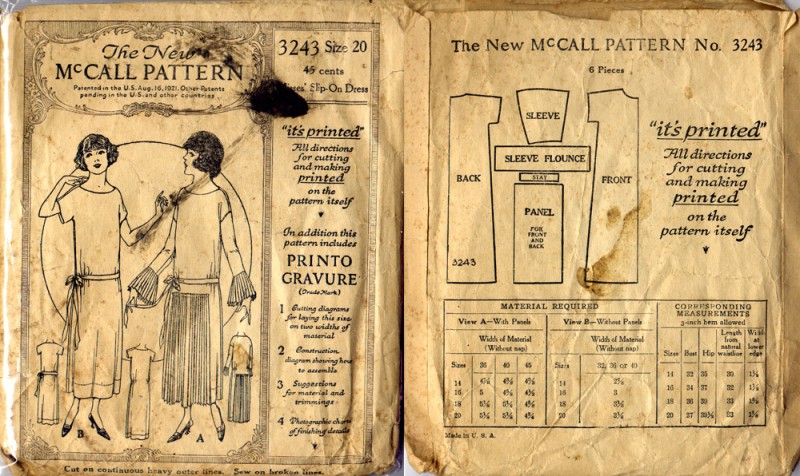

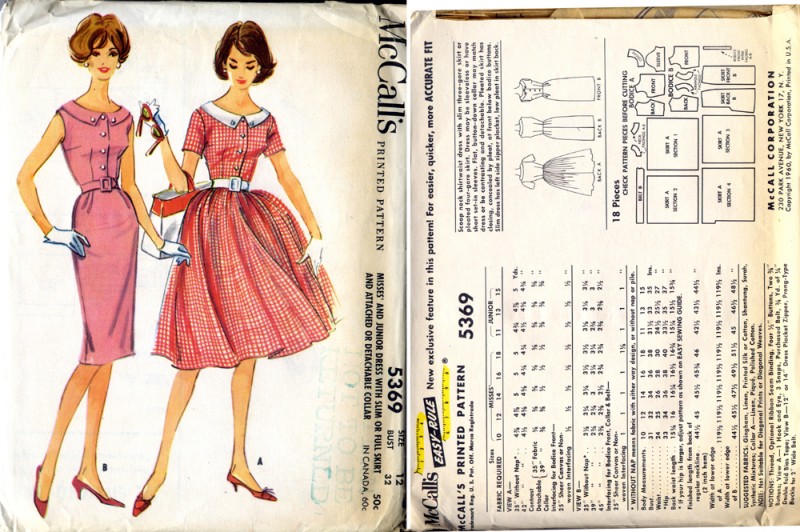

Here we see an envelope from the early 1920s. Notice that it says “It’s Printed” on the outside. From the advent of printing on patterns, until the early 1960s, most printed patterns by any pattern company will say something about including that technology on the envelope. If it doesn’t say “printed”, it’s probably not printed.

The reason McCall started printing their patterns was because they noticed errors in patterns that were cut with the perforated method. Patterns were cut out on a giant press type machine and the holes cut at the same time- often hundreds at a time. Because of this, the patterns at the bottom of the stack often had problems with lining up correctly- some marks would be as much as 1/4″ out of line. Printing was meant to give a perfectly fitting garment with accurate marks, something that wasn’t always the case with the perforated pattern.

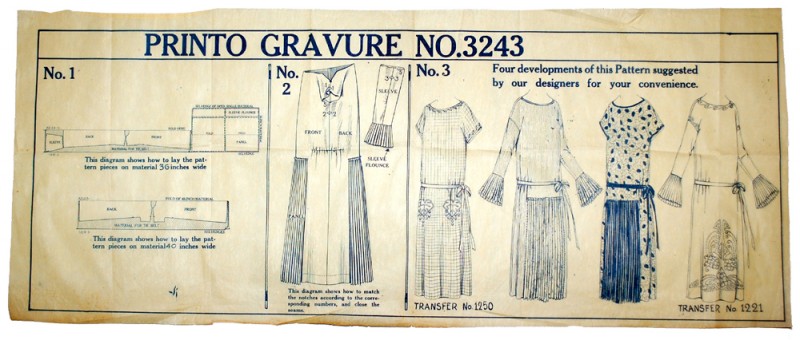

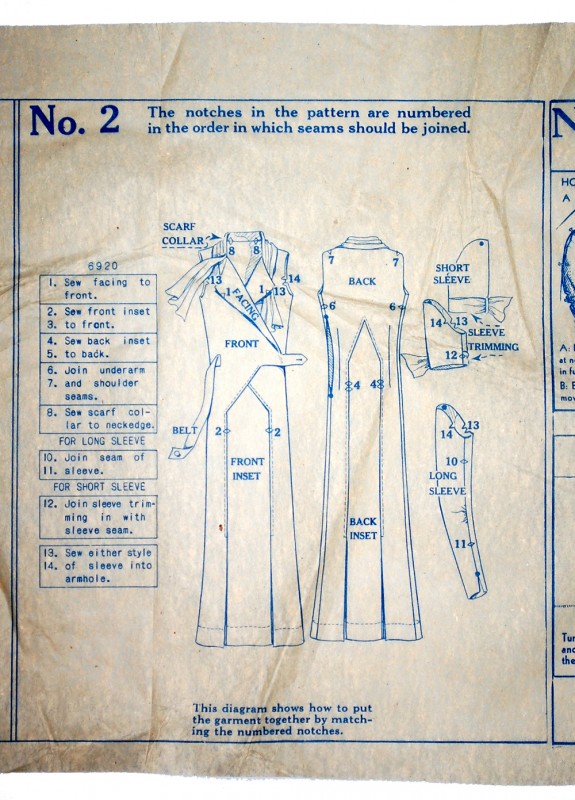

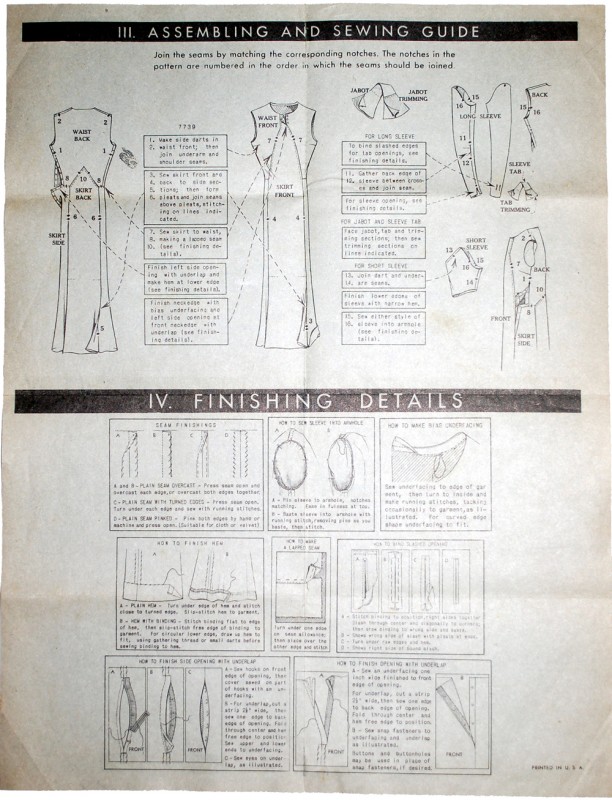

Butterick’s corner on the pattern market was to hold the patent to instruction sheets like we’re familiar with now, with step-by-step illustrated instructions, so McCall did their own version by printing on tissue and inserting it in the envelope. Here you can see the suggestions they give for adding design to this dress- here they suggest getting one of their transfer patterns to use for accents. Instructions for construction were usually a drawing of the finished garment with arrows and numbers for steps- not individual step-by-step drawings like we know today.

Butterick’s corner on the pattern market was to hold the patent to instruction sheets like we’re familiar with now, with step-by-step illustrated instructions, so McCall did their own version by printing on tissue and inserting it in the envelope. Here you can see the suggestions they give for adding design to this dress- here they suggest getting one of their transfer patterns to use for accents. Instructions for construction were usually a drawing of the finished garment with arrows and numbers for steps- not individual step-by-step drawings like we know today.

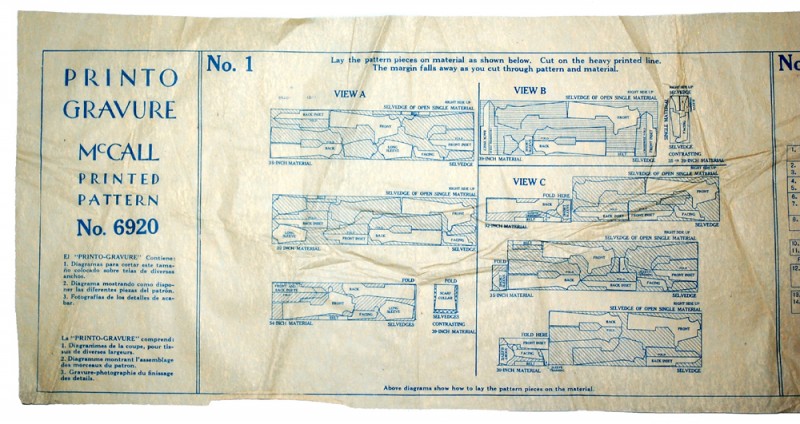

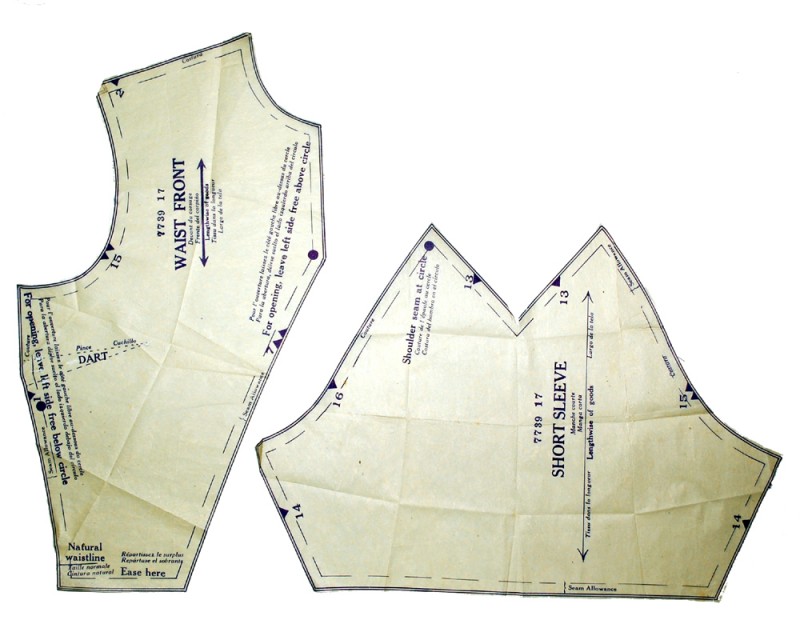

Here you can see part of one pattern piece. On the pattern piece are instructions for finishing. Early McCall printed patterns were printed with blue ink and the instructions were basic and printed right on the pattern envelope.

Here you can see part of one pattern piece. On the pattern piece are instructions for finishing. Early McCall printed patterns were printed with blue ink and the instructions were basic and printed right on the pattern envelope.

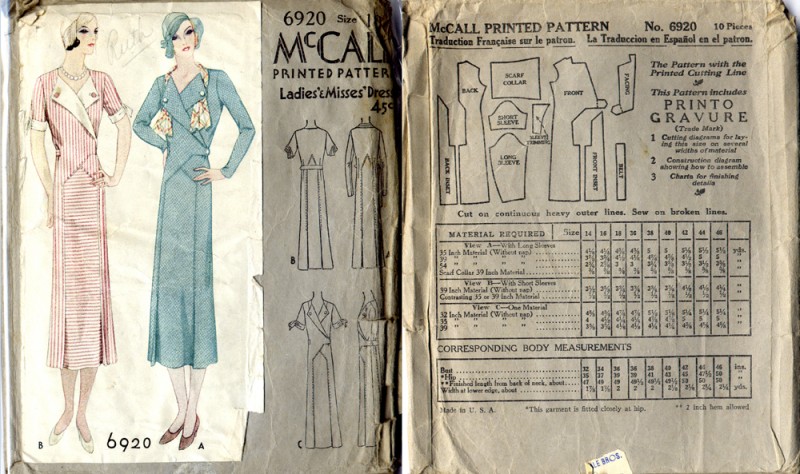

By the late 20s or early 30s McCall added color to their envelopes, as you can see here. This is from 1932. It is important to note, for pattern dating purposes, that when McCall started printing their patterns, instead of doing perforated patterns, they included a copyright date on their pattern envelope. It is also of note that McCall was the only pattern company to include a copyright date on their pattern envelopes during the 1930’s. The exception is the year 1939, when Simplicity started adapting the printed pattern technology, after the McCall held patent expired. Printed patterns by Simplicity are dated 1939. Unprinted patterns by Simplicity did not include a copyright date in 1939.

-A Little Side Track Into Patents-

Patents protect the technological advances, not the actual garment design. Patents would be taken out for envelope layouts, printing techniques, packaging, methods of marking, etc. As long as a patent was in place, the company or person who did not hold the patent could not use the technology. This is why, in early pattern development, certain companies held the patent for printed patterns (McCall), while others had them for step-by-step illustrated instructions (Butterick). It was only after BOTH those patents expired that you saw both of those technological advances in the home sewing pattern industry being available by the same pattern company. Other pattern advances were patented, but instructions and pattern printing were the big ones that changed and shaped the industry. A patent date would last for 17 years from filing date (current patent term is 20 years from filing date). Patent dates ARE NOT the same as copyright dates, so are not an accurate way to date vintage patterns. Now, back to where we were…

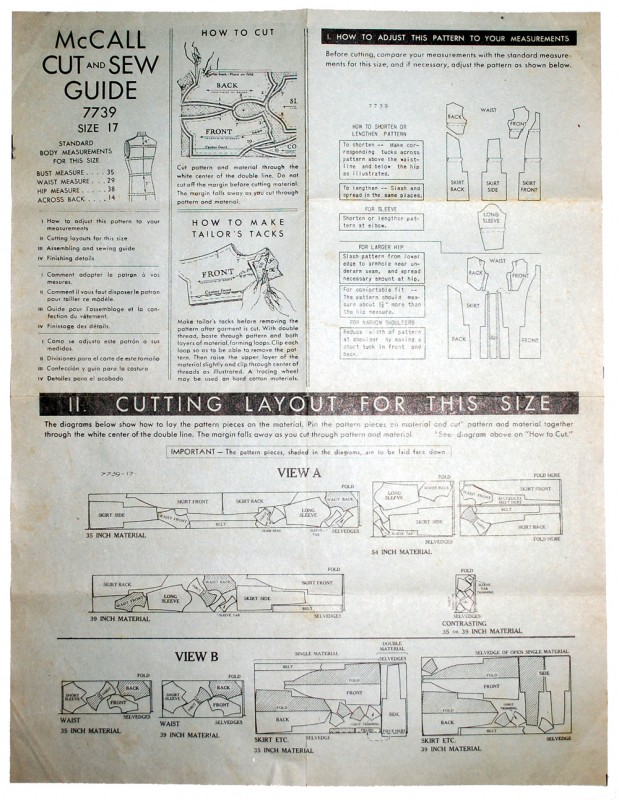

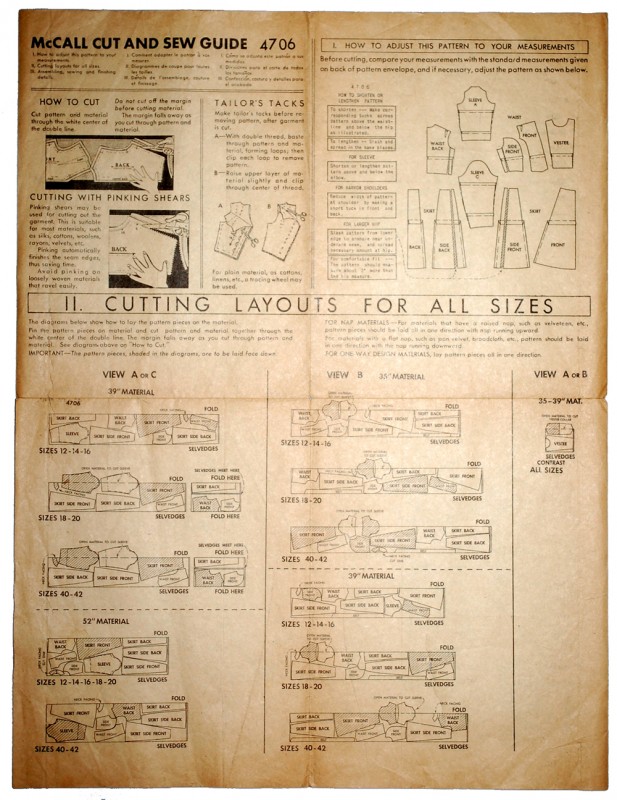

The instructions were still printed on the pattern pieces, though there is more information included now than there were in the 1920s patterns. Below can see a cutting chart.

Below you can see the instructions for putting the dress together. Vintage instructions assumed you knew how to put a garment together with little help, since most women learned sewing in school or from their family. Another way to learn was by book- and sewing books and sewing instructions had different purposes, just like today. The instructions told you basically what steps went in what order, and the book would teach you technique.

Basic finishing was included in the instructions, however, as you can see here.

At this time the patterns were still printed with blue ink, but that was soon to change to a more familiar looking printed pattern to our eye.

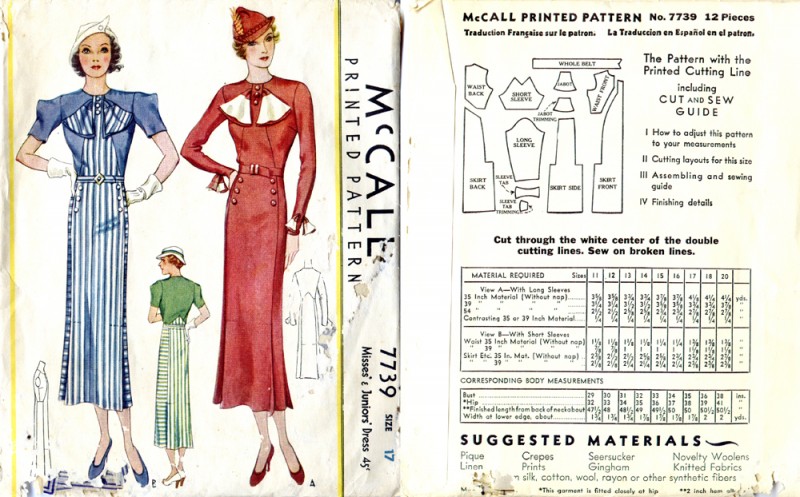

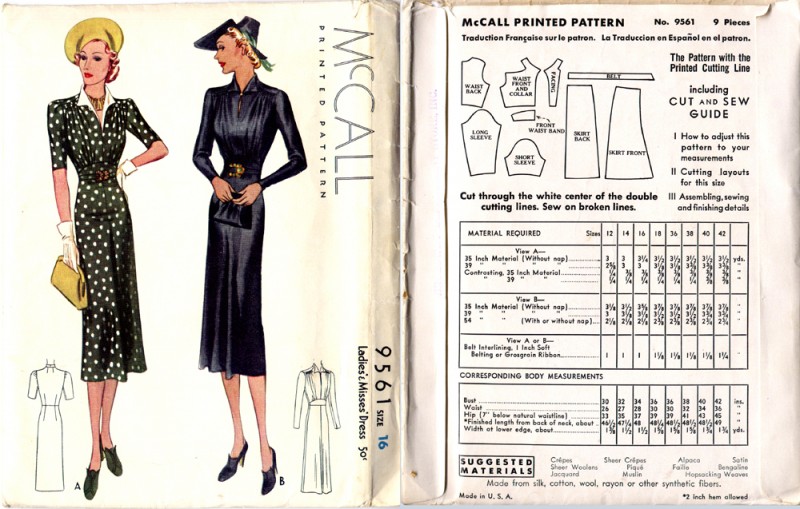

By the early to mid 1930s McCall moved on to another form of printing. Here’s a cover image from 1934, two years after the pattern we just looked at. You can see the color cover image is now printed directly on the envelope, not pasted on, like the prior envelope.

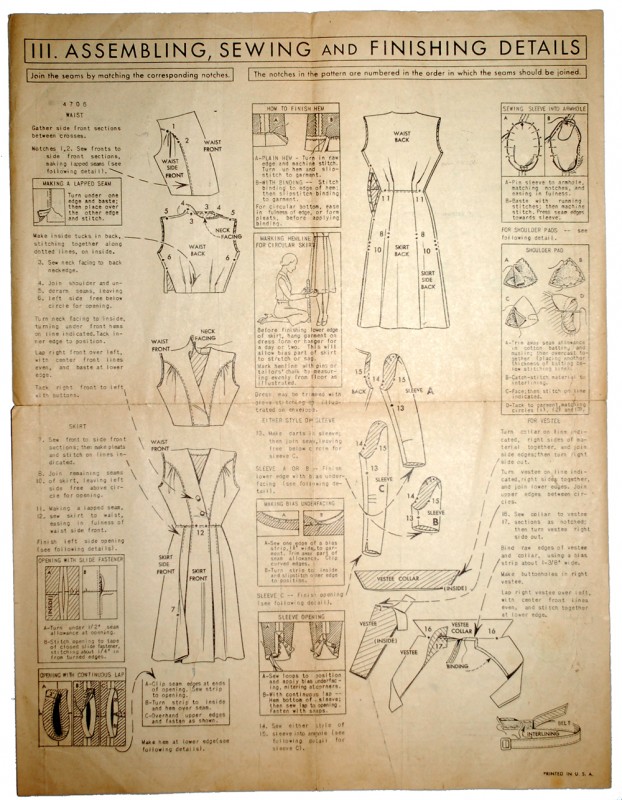

We now have a separate instruction sheet, too- though the content still looks like it did on the tissue paper counterpart of two years ago.

We now have a separate instruction sheet, too- though the content still looks like it did on the tissue paper counterpart of two years ago.

But the pattern is now printed with a double set of outside lines called a “cutting margin”, which was meant to ensure accuracy. The sewer was meant to cut right down the middle of the two lines to get an accurate cut.

But the pattern is now printed with a double set of outside lines called a “cutting margin”, which was meant to ensure accuracy. The sewer was meant to cut right down the middle of the two lines to get an accurate cut.

McCall printed patterns didn’t change again until the 1950s, but we’ll take a quick look at cover design from this point until the 1960s so you can see the way the design changed. The seam allowance, however, did change. It was 3/8″ from the Edwardian era until the early 1940’s, and then it changed to 1/2″. During the later 1940’s, it would change again to 5/8″.

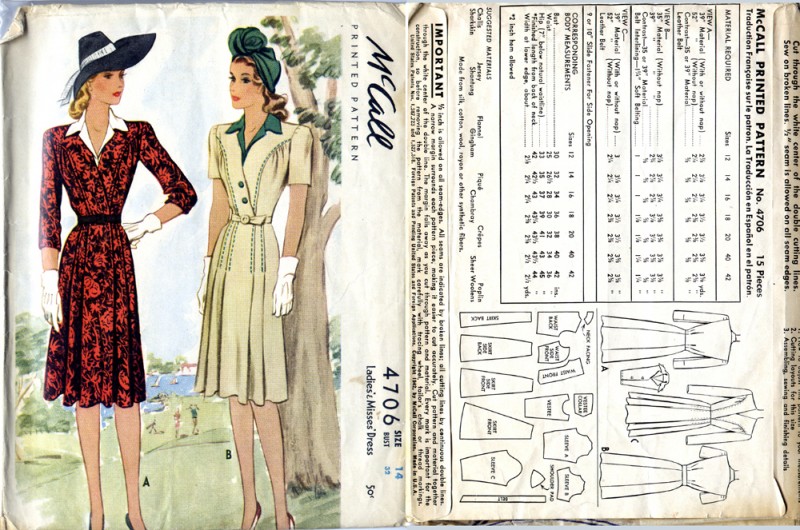

By this time, McCall had more advanced instruction sheets. The patent with Butterick was expired, so McCall started adapting the step-by- step instruction method as well. McCall patterns from the early 1940s and later are much more familiar to use than other vintage patterns because by this point they combined these techniques we take for granted today.

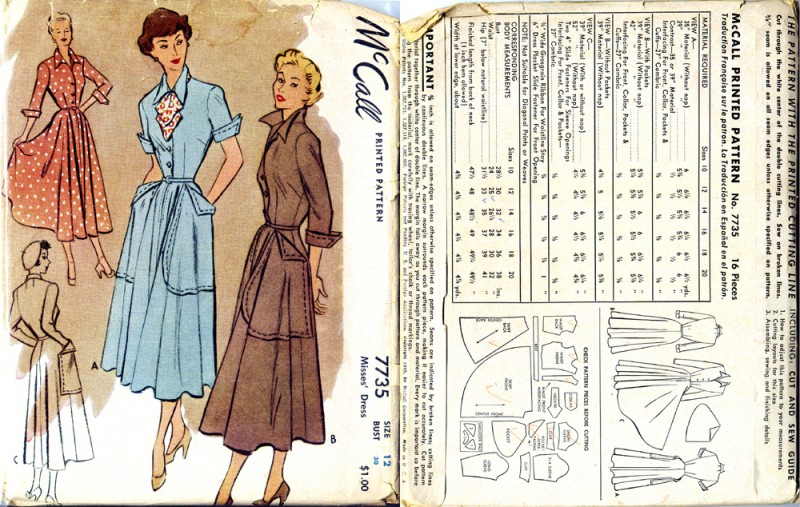

Continuing with the cover art changes and cover layout changes, here’s an envelope from 1949

From 1955. Notice now they are McCall’s with an “apostrophe S”.

And from 1960. But notice it still says “printed patterns” on the cover.

We will stop at 1960, since my area of experience also stops around then. What I would like you to notice, is also the information on the back covers of these envelopes and how it changed. Layouts changed, but also measurements. The silhouette changed based on how fashion dictated, and often proportion was changed due to undergarment structure.

I will continue this series by taking a look at other pattern companies next time. In the meantime, feel free to comment below to let me know any thoughts, questions, or comments.

Debi

December 9, 2013 at 2:15 pm (12 years ago)FABULOUS post!! Oh, how I love McCall patterns!!

Lizzie

December 9, 2013 at 2:58 pm (12 years ago)Excellent information! I’m looking forward to part 2.

Renée

December 9, 2013 at 3:08 pm (12 years ago)What a great post! Thank you so much for sharing your knowledge. I am very eager to read the rest of them. One small comment though, you say McCall changed their seam allowances to 5/8 during the 50s but I have a pattern from 1948 with a 5/8″ seam allowance! I thought it was interesting since it is the only pattern I have from the 40s with a 5/8″ seam allowance in stead of 1/2″.

Lauren

December 9, 2013 at 4:05 pm (12 years ago)Ah! Thanks so much for catching that! I did mean to put later 1940’s, but I had a typo. Thanks so much!

Esz

December 9, 2013 at 3:45 pm (12 years ago)Its funny, I MUCH prefer vintage patterns – and generally avoid new and reproduction and even indie pattern companies at all cost. I dont find the extra sewing information useful at all. And two pages of instructions!? What? Not to mention the horrible pattern paper that is flimsier than my 70 year old Mccalls and even more impossible to fold back into its original shape.

Dont even talk to me about the excess ease either.

So really – I don’t understand the fear for vintage patterns. Fitting them is easier and I find that the diagrams that come with the patterns will tell you a lot, even if the wording is confusing.

That said, I haven’t done a lot of historical sewing – the 30’s to 50’s is more my bag.

Anyways – this is a fantastic post and very informative. Gotta love those Mccall patterns and their handy guides. Also have noticed a lot of my unprinted patterns are a bit imprecise when it comes to notches and holes. Most of the time the grainline holes aren’t even in a straight line at all!

Stina P

December 10, 2013 at 10:44 am (12 years ago)I still find it so fascinating that you have seam allowances included in the patterns – here in Europe we add them ourselves. (Something I prefer since I usually want different allowances on different seams.) But very interesting that they have changed with time.

ByLightOfMoon

January 3, 2014 at 11:52 am (12 years ago)What a lovely post! Thanks for sharing this information and I adore the photos!

Smiles, Cyndi